What to do if your Child Struggles with Mistakes

Preschoolers are learning how to write their name, how to take turns, how to create and play as a group. Preschoolers are learning how to count, tie their shoes, ride a bike. Adults make mistakes throughout their day and they’re supposed to be the competent ones! For little people who are still working to master many skills, mistakes happen all.the.time.

Research suggests that approximately 10% of preschoolers experience anxiety (Egger & Angold, 2006 as cited in Milan, Godoy, Briggs-Gowan, & Carter, 2012). Children with anxiety can experience increased difficulty making mistakes – especially if they fall more into the ‘perfectionist’ category. But let’s remember, these are preschoolers - it is expected for them to make many, many, many mistakes.

For children who struggle with making mistakes, this can be incredibly problematic. Some children ‘shut down’ and become unresponsive. Others refuse to acknowledge that they made an error – often insisting that whatever happened was somebody else’s fault. Some have large, emotional, responses to mistakes. All of these responses and reactions make peer engagement and participation in group activities more challenging (do you like to hang out with people who cannot acknowledge when they made a mistake?). Even more importantly, it doesn’t feel good to the child.

“Calmly and confidently making mistakes is a skill - which means it can be taught and improves with practice.”

On the one hand, children are expected to repeatedly make mistakes while learning new skills. But on the other hand, it feels completely unbearable to make mistakes. So what can we do? Calmly and confidently making mistakes is a skill – which means it can be taught and improves with practice. I’ve outlined seven strategies to help children better understand mistakes and to reduce some of the emotional response associated with making mistakes.

Eight Ways to Help Your Child Calmly Make Mistakes

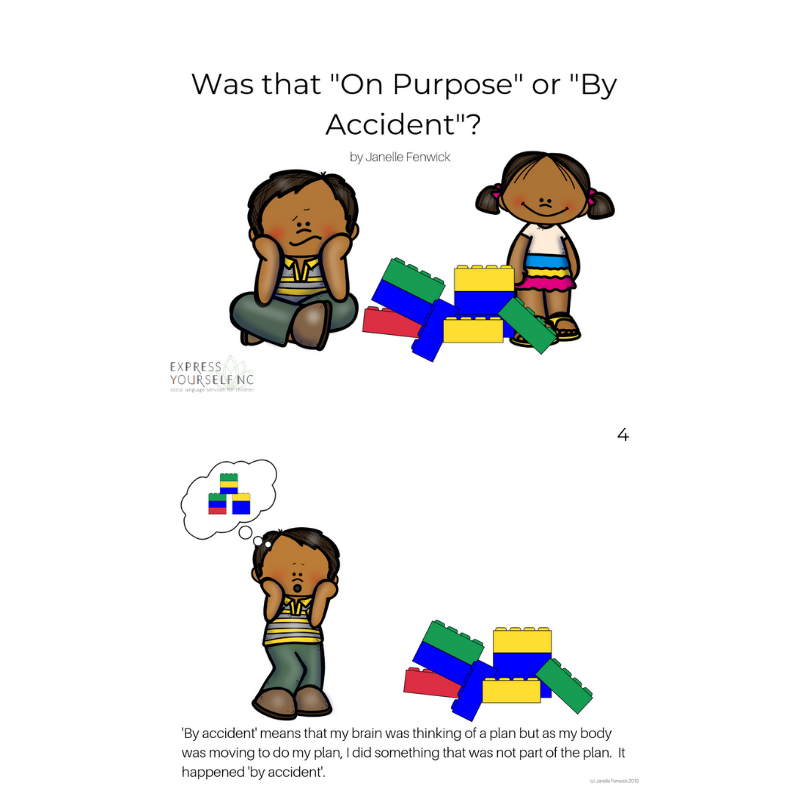

1. Explain the difference between doing things ‘by mistake’ and ‘on purpose’

The first step is to help your child understand what a mistake is and how they happen. I’ve written a social story outlining the difference between doing things ‘by accident’ and ‘on purpose’. It’s completely free and you can download your copy of Was that “On Purpose” or “By Accident”? here. The quick read: when something happens that our brain wasn’t thinking about doing – it wasn’t ‘on purpose’, it was ‘by mistake’.

2. Draw Attention to your Own Mistakes

Yup, this is a super comfortable one ;-). Parents, teachers, and caregivers are the best models. During life, when you make a mistake, draw attention to it. The key here is to be factual about what happened. Consider the difference:

“Gah! I can’t believe I spilled coffee everywhere. Now we’re going to be late and I have to change. I’m so stupid. I can’t believe I did that again”

versus:

“I spilled my coffee, that was a mistake. I was thinking about getting my keys and bumped my coffee instead, whoops”

I know, it’s easier said than done because mistakes can be incredibly frustrating. However, if we as adults, cannot control and alter our own responses and reactions to mistakes then is it really fair for us to ask the same of children?

3. Notice all the things you do ‘on purpose’

Mistakes can feel larger since they can be more obvious. While most people make at least one mistake a day, everyone is also successful and purposeful thousands of times. It can be hard to notice all the things that we do ‘on purpose’, so it’s about time we start making it more obvious ;-).

When you’re doing things, verbalize that you did that action ‘on purpose’ – you were thinking about doing it and then you did it. Do the same to draw attention to things your child does ‘on purpose’.

It can be tricky to figure out how to phrase these types of statements (this is a skill, you’ll get better with practice!). Try using this format:

“You *action* on purpose. You were thinking about *action* and you did it!”

“Wow, you built that tower so high on purpose. You were thinking about making a tall tower and you did it!”

“I got a paper towel to dry my hands on purpose. I was thinking about getting a paper towel and I did it”.

Initially it might seem silly to draw attention towards intentional acts – especially ‘small’ things (like drying your hands) – the goal is to help notice that we successfully do intentional things constantly.

4. Learn about famous mistakes

The slinky, silly putty, post-it, all created because someone made (and explored) a mistake. Explore some famous mistakes to notice how people responded to the mistake. Consider what would have happened if the mistake was never ‘claimed’ or even explored!

5. Practice making mistakes

So technically if you’re practicing making a mistake it’s not really a mistake (mistakes are unintentional). But we know that responding to mistakes in a calm fashion is a skill – and skills we can improve and learn through practice. For more about learning and teaching the difference between skills and luck, download the free social story ‘Did that Happen Because of Skill or Luck?’.

Practicing making mistakes supports a discussion about a challenging topic outside of an actual challenging time. I like to start by first highlighting my own mistakes during a task. I then ease into outlining that I’m actually going to practice making mistakes.

Ideally you practice mistakes using similar situations that are tricky for your child (individualizing is so important!). Common ‘high mistake frustration’ activities include: art, block building, Legos (seriously, how frustrating is it when your Lego creation flies apart as you try to put on a piece!?!?!).

6. Read books about making mistakes

Books serve as a ‘safe space’ to explore more challenging ideas. It can feel more comfortable to talk about mistakes when you’re talking about a character’s mistakes.

Check out How to Use Books to Support Children in Making Mistakes for more ideas for how to begin this conversation and ways to use these amazing books.

7. Recognize hard work and practice

Successful end products more naturally tend to be celebrated. It’s less common for people to celebrate hard work and practice – and yet it’s the hard work and the practice that helps us ultimately achieve the end products! Give positive comments for practice and hard work.

As you see your child working on a puzzle, comment on how many ways they tried to make their piece fit or how hard they worked to make a piece fit - “I noticed you working to find where that piece belonged. It looked tricky but you kept at it”.

8. Highlight what you are practicing and learning

We want our children to be comfortable practicing, making mistakes, and learning. So again, we must model those actions ourselves. Think about something you’re working towards – a personal goal or something that is hard for you. Perhaps you’re working to run a certain number of miles or to cook a new dessert. If your job requires assessments or continuing education requirements, let your children know when you’re studying for tests or working on developing these new skills.

So there you have it:

Eight ways to help your child feel more confident to make mistakes

Two social stories (Was that ‘By Accident’ or ‘On Purpose’? and ‘Did that Happen Because of Skill or Luck?’)

One book list for books all about making mistakes

Let us know which ones you try and how it goes!

Citations:

Mian, N. D., Godoy, L., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., & Carter, A. S. (2012). Patterns of anxiety symptoms in toddlers and preschool-age children: evidence of early differentiation. Journal of anxiety disorders, 26(1), 102–110. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.09.006